As a professor and therapist, I see many people come through the door who struggle with a variety of feelings they identify as problematic to their lives: depression, anxiety, mania, suicidal thoughts, panic, grief, anger (and so on). We are taught, as therapists, to see the cycles of mood as an inherent problem—something indicative of a “mood disorder,” something to keep high alert about, to monitor, to control, to consider medicating. While I do not deny the existence of some cyclic mood disorders—where people experience “episodes” of severe negative feelings or intense anxiety that cause notable distress—it does seem problematic, both within and outside of therapy, that people so often consider cycles detrimental.

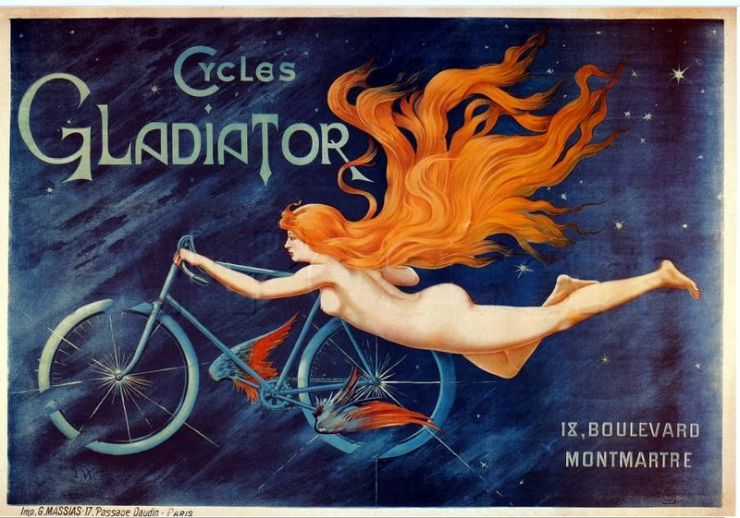

Never is this disdain of cycles more evident than in people’s descriptions of women’s menstrual cycles as inherently troubling. Women feel more moody, less energetic, more bloated, angrier, less sexual, hungrier, more tender (and men, too often, quickly hurl these cyclic changes into women’s faces as an insult). This bothers women, they say, because they like to feel “normal” (that is, emulating men who supposedly lack emotional and physical cycles). But, isn’t the fundamental nature of things quite…cyclic? Nearly everything that comes in cycles has benefits, teaching us that the world is non-static, ever-changing, always in flux. The changing seasons (even here in Phoenix, where the seasons move from pleasantly warm to unbearably hot) signal the onset of new weather patterns, shorter or longer days, and necessary difference. Growing up in the West, I have heard East Coast and Midwest people lament the loss of changing seasons when they move to California or Arizona—they want the rhythms, pace, and visual scenery that accompanies the traditional four seasons existence.

We are creatures that crave cycles, I think. Academics rely on the ebbs and flows of the academic year to guide their work, pausing in the summer and over the holiday break for some much-needed rest before starting again each school year with full gusto. College professors’ job satisfaction is among the highest in all professions, alongside computer programmers, who overwhelmingly set their own hours, and physical therapists, who have more autonomy than most American workers. (Cross-culturally, European workers generally report more happiness as well, as Europe generally recognizes the cyclic nature of life by offering extended vacation time, paid maternity leave, and generous sick pay.) More and more American companies have started giving employees period “sabbaticals”, acknowledging that larger chunks of time to shift focus, relax, start a new project, or travel will earn company loyalty and will markedly increase job satisfaction. The monotony of the year-round 9-5 job with little vacation time and, more importantly, no cycles of work and play, creates the most havoc on people’s lives. Shift workers who disrupt the natural cycles of their bodies—staying up all night, sleeping all day—have poor life expectancies, substantially higher risk of at least six different kinds of cancer, more heart attacks, and far poorer health outcomes as a result. Even those who take anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medication—perhaps to lift them out of their low moods or panicky states—often report feeling apathetic and robotic as a side effect, missing, it seems, the cycles of mood they once had.

I would argue that the disdain for cycles, the need to convince people that they should never feel too sad nor too happy, the loathing we seem to direct toward the menstruating body, the insistence that people work themselves to death without breaks or cyclic expenditures of energy, results from the dangerous fusion of patriarchy, capitalism, and the pharmaceutical industry. The dogged insistence that people must always be happy, must work until they drop without ever taking time to fully rest, must always “manage” the cycles of their bodies (for example, losing their “baby weight” right after pregnancy, controlling menstrual blood, forcing themselves to work following a death in the family, clocking in the same hours year round), reveals a deep-seated disavowal of cycles as fundamental to human life. Cycles matter—they reflect the truths women have always known, the necessity of change and movement, the power of the body to teach us about the world and, perhaps, to undermine the institutions that deplete and eradicate the natural cycles of human life in favor of sexism and profit.

This was exactly what I needed to hear this morning, Breanne, thank you! This disdain for cycles and the need to push ahead at all times (pretending life is a linear experience and that if we stop or change we are going backwards) is so responsible for all of the guilt we feel in life and the lack of confidence we have in ourselves on a daily basis. Thanks for this post! I feel better already today!

Yes! Made my day too. Thank you Breanne.

I recently had this image of our cyclic lives as a three dimensional holographic spiral we travel along – where we can look up or down and see where we’ve come from and where we’re going. And that we sometimes return to a place on the spiral but have new insight to re-inform and re-animate our journey.

Enough of the plodding along experience of life! It’s clearly not healthy for our psyches.

Yes! This is amazing! Thank you!